The End of U.S. Dollar Privilege

I’m on a currency kick, so forgive my persistence.

But currencies factor into economic growth, inflation, bond, stock, and commodity markets—heck, everything.

They compose an integral part of the massive informational network called Price. So, understanding how exchange rates relate to capital markets is essential to an investor’s decision-making framework.

And to grasp that relationship, it helps to study how currency markets evolved in the first place.

As I explained Wednesday, the U.S. dollar has played a significant role in America’s economic dominance since the end of WWII.

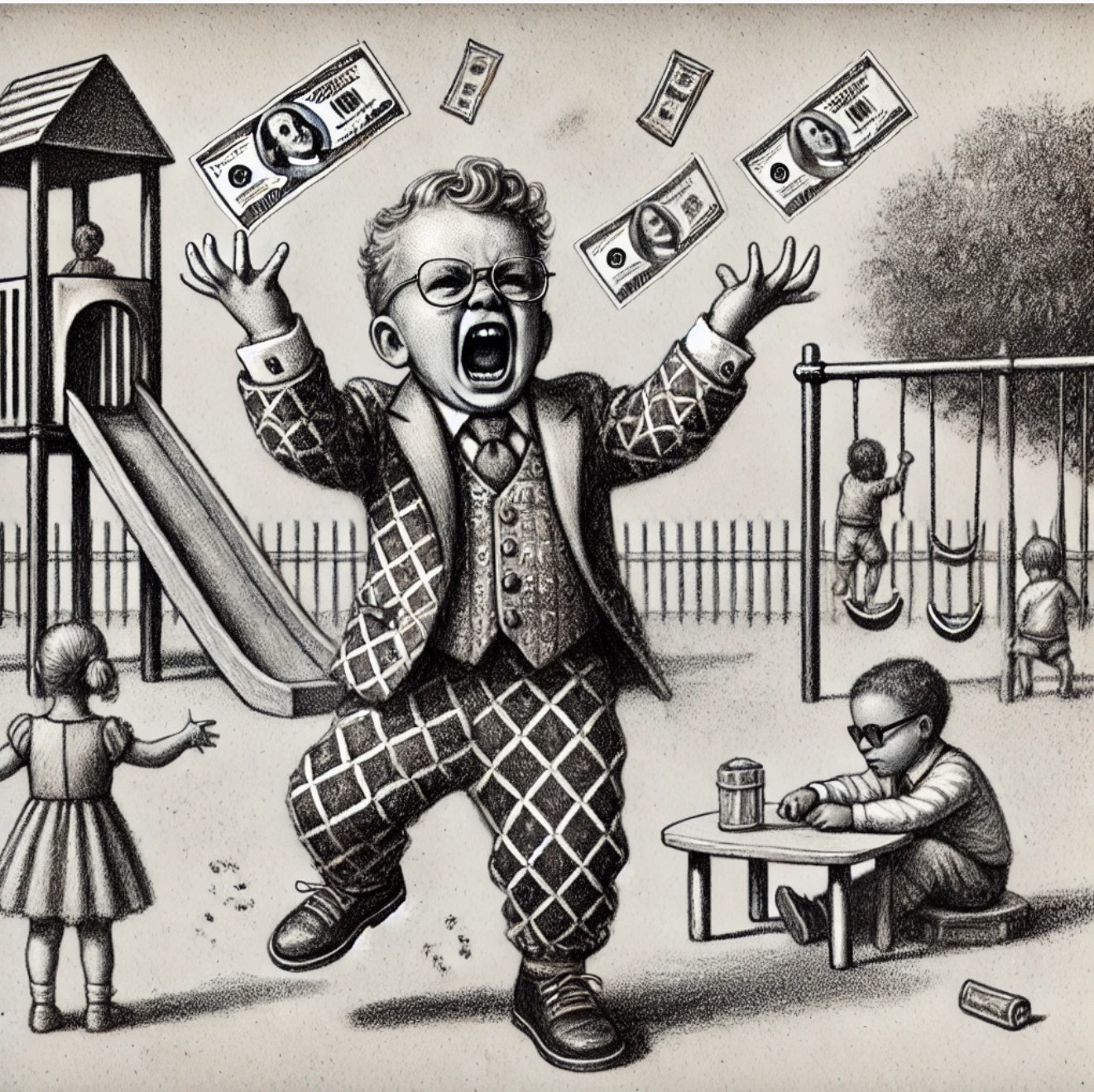

Our nation’s currency has held a privileged role ever since, giving American companies a massive competitive edge, helping the U.S. government dictate foreign policy, and providing Americans with a high standard of living that came, in large part, at the expense of the rest of the world.

In the 60s, the French labeled that privilege “exorbitant.”

And understanding the French’s complaints at the time will help you see how the era of Exorbitant Privilege could finally be coming to an end.

Calling America’s Bluff

“The United States has an exorbitant privilege to turn its dollar into a worldwide currency with no restriction. That’s something that no other country can do. But it’s something that is in the process of ending.”

Those were the words of French Minister of Finance Valéry Giscard in the 1960s regarding the exorbitant privilege that the U.S. dollar had maintained since WWII.

He was wrong about it being in the process of ending. Or, at least, very early.

But he was right about “exorbitant privilege.”

It worked like this.

The Bretton Woods System pegged the U.S. dollar to gold, and foreign governments could exchange dollars for gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce.

However, countries didn’t actually convert. They let the U.S. dollars pile up, keeping the market supply of dollars low and its exchange rate high.

And a strong exchange rate allowed the U.S. to export inflation to the rest of the world.

How exchange rates transmit inflation is a topic for another day, but inflation transmission was the essence of the privilege.

A privilege that the U.S. government abused.

It ran up massive government debt to fund the Vietnam War and Johnson’s massive welfare-state expansion during the 60s.

That debt expanded the money supply, ultimately landing on foreign central bank balance sheets as U.S. dollar reserves.

De Gaulle, France’s president, sought to end this privilege by using the system as intended. He threatened to redeem France’s reserves for gold.

He was calling America’s bluff. He knew the U.S. didn’t have nearly enough dollars to meet its commitment.

So, when the redemptions began flooding in, Nixon played his trump card – he ended the system.

On August 15, 1971, Nixon announced that the U.S. would suspend the convertibility of dollars into gold, effectively ending the gold standard and the Bretton Woods system.

This move allowed the dollar to float freely against other currencies, leading to the current system of fiat currencies and floating exchange rates.

It was the end of the system, but not the end of America’s exorbitant privilege.

We found a way to extend the game.

And tomorrow, I’ll show you how the unraveling of agreements that extended that game signals the end of an era for the U.S. dollar.

Related ARTICLES:

Adjusting to the Fed’s New Reality

By Don Yocham

Posted: November 15, 2024

A New Game Just Like the Old Game

By Don Yocham

Posted: October 20, 2024

The End of U.S. Dollar Privilege

By Don Yocham

Posted: October 19, 2024

FREE Newsletters:

"*" indicates required fields